Social and emotional understanding and skills underpin both personal resilience and healthy relationships. Howard Gardner (1999) identified the two intelligences as intrapersonal—understanding and managing the self, and interpersonal—establishing and maintaining positive relationships. Although the following list is not exhaustive, the authors identify SEL as including the following:

- recognizing and labelling personal feelings, strengths, and values

- knowing how to regulate and express feelings effectively and safely

- having a prosocial orientation to others, which is not bound by prejudgment

- being able to read and take account of the emotional content of situations

- being responsible to oneself and others and making ethical decisions

- being able to set goals in both the short and longer term

- problem-solving skills, especially in the domains of personal coping and interpersonal relationships

- focusing on the positive

- respect for others, including valuing diversity

- treating others with care and compassion

- good communication skills

- knowing how to establish, develop, and maintain healthy relationships that promote connection between individuals and groups

- being able to negotiate fairly

- having skills to deescalate confrontation and manage conflict well

- being prepared to admit mistakes and seek help when needed and

- having personal and professional integrity demonstrated by consistently using relational values and standards to determine conduct

Although these competencies are written here as separate, they are dynamic and overlapping, and always in interaction with specific contexts (Triliva & Poulou, 2006). This makes the teaching of such skills complex and highlights the importance of pedagogy and teacher skills. Social and emotional learning may focus not only on the acquisition of knowledge and skills as in other subject areas, but also in changing or developing values, beliefs, attitudes, and everyday behaviors. As can be seen from the above list, SEL is not just about individual well-being but also about the development of healthy relationships and caring communities. SEL takes root when it is embedded within whole-school practices that support school connectedness and student well-being. The congruence of the values and ethos of a school are critical to embedding such learning across the whole school community (Roffey, 2008).

Research and Effective Programs for SEL

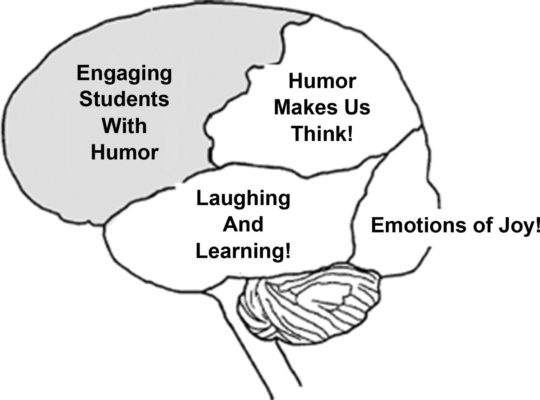

Indications are that higher levels of SEL or emotional literacy can reduce subjective stress and increase feelings of well-being (Slaski & Cartwright, 2002), improve coping abilities, (Salovey, Beddell, Detwieler, & Mayer, 1999), limit drug and alcohol addiction (Trinidad & Johnson, 2002), mediate aggression (Jagers et al., 2007), enhance psychosocial functioning (McCraty, Atkinson, Tomasino, Goelitz, & Mayrowitz, 1999), increase school connectedness (Whitlock, 2003), reduce bullying (Bear, Manning, & Izzard, 2003), and increase the capacity of students to learn (Zins, Weissberg, Wang, & Walberg, 2004). These results reinforce earlier research indicating that children’s peer relations in school predict school success (Ladd & Price, 1987). The finding that children’s social competence develops in the context of interacting with their peers is especially important as children of primary school age have fewer opportunities out of school for interacting freely with peers and thus developing social competence (Burdette, 2005).

A plethora of information exists about the need for evidence-based SEL programs, multiyear and integrated programs, principal and staff support, community involvement, coordination, and congruence with caring, school practices (Zins & Elias, 2007). Triliva and Poulou’s (2006) review of studies on competence-based programs, however, reveal a lack of research on teachers’ perceptions or understandings regarding the development or implementation of SEL within school settings. As it is well documented (Alvirez & Weinstein, 1999; Donahue, Weinstein, & Cowan, 2000) that teachers’ implicit theories have a significant impact on their approaches to teaching, teachers’ attitudes toward implementing SEL in schools become crucial.

The literature focuses on what should be taught in some detail but not about the how within the classroom. The training of teachers on the PATHS program mentions both principal support and “implementation quality” (Kam, Greenberg , & Walls, 2003), but provides little clarity about what “implementation quality” means. Much of the language in schools remains based in the realm of targets, instruction, and program delivery. Less information exists on pedagogy—the way in which this learning might come about and the teaching approaches that facilitate both knowledge and skills. Zins and Elias (2007) mention just one: “addressing emotional and social dimensions of learning by engaging and interactive methods.”

However, research has been conducted on what is involved in “transformative” learning—where education is seen as the vehicle for both personal and social change. This is sometimes referred to as “critical pedagogy” and rejects didactic methods of teaching as technical and instrumental. Fetherston and Kelly (2007) explore a pedagogy for conflict mediation, which is itself a feature of SEL in that it requires self and relationship exploration and new ways of thinking and doing. They base their thinking around cooperative learning. When students engage with content at the same time as learning/practicing prosocial skills in collaborative ventures, they are employing basic conflict resolution skills to make their learning groups effective. When students are asked to reflect on group processes and skills, they are able to connect them to the course content and then to wider, deeper issues. “Through changes in understanding and perspective, through the reframing of ‘problems,’ personal and social transformations become possible.” P. 264 Fetherston & Kelly (2007) Elias and Weissberg (2000) contend that when SEL activities are coordinated with and integrated into the regular curriculum, they are more likely to have lasting effects. A student who is discussing what a character in a story feels, or what emotion a piece of music or art conveys, is actively developing emotional understanding (Mayer & Cobb, 2000). Reading and discussing stories where the characters have to confront dilemmas with a wide range of feelings, or having students address emotions through role-plays, can provide them with a repertoire of responses to real-life situations (Norris, 2003).